Getting Started with

Folklore & Folklore Studies:

AN INTRODUCTORY RESOURCE

by Joseph S. Hopkins (Hyldyr) & Ceallaigh S. MacCath-Moran (Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador) for Hyldyr, February, 2024

We've all heard the phrase “That's just a myth”. And we’ve also no doubt heard phrases like it with myth swapped out for legend or fairy tale. These words are all often used as synonyms for fiction or falsehood in everyday English conversation. Yet scholars active in folklore studies use the terms quite differently. To folklorists, each is a different category of folk narrative. And to the categories of myth, legend, and fairytale - called genres by folklorists - we can add many more, including ballad, fable, and tall tale. We can also add genres rooted in belief - ritual, superstition, charm, and curse, among others - and we can add genres rooted in material culture and performance, like traditional foodways and traditional music, respectively. Each genre encompasses a wide variety of expressive culture, but folklorists understand that genres themselves can be imperfect methods of categorization and strive to understand the nuances of everything they study. In this resource, we take a quick dive into the formal study of folklore and provide a variety of resources and suggestions for those who want to pursue the topic further.

What do folklorists study?

The simplest and most widely-cited definition of folklore comes from folklorist Dan Ben-Amos, who writes that folklore is “artistic communication in small groups.”[1] This definition encompasses a huge variety of topics, and folklorist Alan Dundes endeavors to detail many of them here:

Although it may not be satisfactory, a definition consisting of an itemized list of the forms of folklore might be the best type for the beginner. Of course, for this definition to be complete, each form would have to be individually defined. Unfortunately, some of the major forms, such as myth and folktales, require almost book-length definitions, but the following list may be of some help. Folklore includes myths, legends, folktales, jokes, proverbs, riddles, chants, charms, blessings, curses, oaths, insults, retorts, taunt, teases, toasts, tongue-twisters, and greeting and leave-taking formulas (e.g., See you later, alligator).

It also includes folk costume, folk dance, folk drama (and mime), folk art, folk belief (or superstition), folk medicine, folk instrumental music (e.g., fiddle tunes), folksongs (e.g, lullabies, ballads), folk speech (e.g. slang), folk similes (e.g., blind as a bat), folk metaphors (e.g., paint the town red), and names (e.g., nicknames and place names). Folk poetry ranges from oral epics to autograph-book verse, epitaphs, latrinalia (writings on the walls of public bathrooms), limericks, ball-bouncing rhymes, jump-rope rhymes, finger and toe rhymes, dandling rhymes (to bounce on the knee), counting-out rhymes (to determine who will be "it" in games), and nursery rhymes.

The list of folklore forms also include games; gestures; symbols; prayers (e.g., graces); practical jokes; folk etymologies; food recipes; quilt and embroidery designs; house, barn, and fence types; street vendor's cries; and even the traditional conventional sounds used to summon animals or to give them commands.

There are such minor forms as mnemonic devices (e.g., the name Roy G Biv to remember the colors of the spectrum in order), enveloped sealers (e.g., SWAK—Sealed With A Kiss), and the traditional comments made after emissions (e.g., after burps or sneezes). There are such major forms as festivals and special day (or holiday) customs (e.g., Christmas, Halloween, and birthday).

This list provides a sampling of forms of folklore. It does not include all forms. These materials and the study of them are both referred to as folklore. To avoid confusion it might be better to use the term folklore for the materials and the term folkloristics for the study of the materials. [2]

Since Dundes's essay was written, many new varieties of folklore have arisen, including those born on the Internet, such as copypasta.

Finally, it is important to note that folklorists do not simply study text, they also study context and performance. For example, the study of an urban legend would include various versions of the text itself, the communities where they are told, the tellers, and their audiences. For this reason, folklorists often think of folklore as a communicative process. [3]

2. What is folklore?

In general, tradition and communication are among the foundations of folklore, and these are complex concepts. To understand their place in folkloristics [4] a little better, consider the ways Ben-Amos’s “artistic communication in small groups” corresponds with the definition provided by the Oxford English Dictionary:

The traditional legends, beliefs, culture, etc., shared by a group of people, esp[ecially] a rural or pre-industrial society; the study of these. As well as stories, proverbs, etc., passed down orally, folklore can include other traditions such as material culture, customs, rituals and dances. Frequently with modifying word indicating the relevant community, nation, or region. (Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “folklore, n., sense 1”, July 2023. (https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/9786880905)

Next, consider the more expansive definition offered by folklorists Robert A. Georges and Michael Owen Jones:

As we interact with each other on a daily basis, we continuously express what we know, think, believe, and feel. We do so in a variety of readily distinguishable, often symbolic ways: by singing and making music, for example, or by uttering proverbial expressions, dancing, and creating objects. Much of what we express and the ways we do so have the behaviors of our predecessors and peers as sources. We learn most of the stories we tell and the games we play not in the classroom or through print or other media, but rather informally and directly from each other. With time and repetition, some examples of human expression become pervasive and commonplace. When they do, we conceive them to be traditions or traditional; and we can identify them individually or collectively as folklore.

The word folklore denotes expressive forms, processes, and behaviors (1) that we customarily learn, teach, and utilize or display during face-to-face interactions, and (2) that we judge to be traditional (a) because they are based on known precedents or models, and (b) because they serve as evidence of continuities and consistencies through time and space in human knowledge, thought, belief, and feeling. The discipline devoted to the identification, documentation, characterization, and analysis of traditional expressive forms, processes, and behaviors in folkloristics (alternatively identified as folklore studies or folklife research). Those who are trained in that discipline and who pursue its objectives in their work are folklorists.

Folklore is an integral and vital part of our daily lives. In stating that our hands are “as cold as ice” or that a room is “as hot as an oven”, we speak folkloricly, using familiar, widely disseminated proverbial comparisons. In order not to “tempt the Fates,” many of us knock on wood when we mention our well being or ongoing successes perpetuating a practice that has [ancient roots]. (Georges & Jones 1995:1)

While this is a textbook definition—literally, it’s taken from the first page of Georges’s and Jones’s Folkloristics: An Introduction—the complexities inherent to folklore do invite debate among folklorists. Still, most would agree that the definitions above provide an appropriate level of introduction to the topic. [5]

Ultimately, the scholars cited above assure us that folklore and the study of it are as broad as human culture itself. For example, a simple reference to ghosts may be categorized both as narrative and supernatural belief, and it may further be studied in the context of the community from which it was collected. [6] A traditional recipe may be categorized as an element of material culture and studied in the context of present and past community cooks. Even a phrase like “knock on wood” has more than one place in folkloristics: as verbal lore, supernatural belief, and ritual. Human beings encounter folklore every day, in workplace humor, Internet memes, family stories, and elsewhere. Folk belief, narrative, and performance are still with us, even though we live differently from our pre-industrial forbears. Whenever we engage in “artistic communication in small groups,” we continually renew the expressive culture folklorists analyze.

3. Ghosts of the Past & Ghosts of the Present

Let us return to our friend the ghost for a deeper discussion of folkloristics in practice. The concept of the ghost is complex and comprised of many shifting cultural associations. People all over the world believe or disbelieve in these supernatural beings, [7] and we can use a folkloristics of belief to discuss their perspectives with them. Memorates [8] or legends about ghosts can be analyzed using a folkloristics of narrative, and so can popular phrases like “she was ghosted.” We can even use a folkloristics of performance to understand legend-tripping at haunted houses. But how does this contemporary folkloristic toolkit help us understand historical ghostlore?

We can begin to answer this question by considering the language we’re using here, English. The modern English word ghost descends from Proto-Germanic, and comparative evidence from other Germanic languages strongly implies that early speakers [9] had a conceptual understanding of ghosts that was similar to ours. [10] Unfortunately, no narrative among ancient Germanic-speakers survives about these entities. [11] However, we can find stories among the distant linguistic cousins of these peoples, such as speakers of Latin in the Roman Empire. For example, a letter from Roman writer Pliny the Younger to Roman senator Lucius Licinius Sura contains a remarkable ghost story that may sound familiar to readers even though it is over 2,000 years old:

There was, at Athens, a house, large and spacious, but with a bad name. In the silence of the night, there was wont to be heard in it the rattling of iron, and, if you listened more attentively, the clash of chains, first at a distance, then hard-by.

Presently there appeared a ghost—an old man, lean and squalid, with long beard and rough hair. He carried fetters on his legs and [shackles] on his wrists, shaking them as he walked. Hence every night was spent in wakeful terror by the inhabitants.

Sickness followed vigils, and death sickness. For even during the daytime, though the phantom had departed, the recollection of it clung to them, and the terror lasted longer than that which caused it. Accordingly the house was deserted, condemned to solitude, and entirely given up to the spectre. It was advertised, nevertheless, to be let or sold, in case anyone, not knowing the circumstances, should be willing to purchase.

Athenodorus, the philosopher, came to Athens, read the notice, asked the terms, and, having his suspicions roused by the low price, made inquiries, and heard the whole story. So far from shrinking, he took the house all the more eagerly.

When evening drew near, he orders his couch to be placed in the front room, calls for a writing-tablet, a style [a writing instrument], and a light, dismisses all his attendants, and devotes his attention eyes, head, and hands—to writing, lest his mind, being unemployed, should conjure up fancied sights and sounds.

At first there was the silence of night, deep as elsewhere; then the clash of iron and the rattling of chains. He neither raised his eyes nor relaxed his style, but fixed his attention upon his work.

The clink grew louder, came nearer, and sounded, now at the door, now within the room. He looks up, sees and recognises the spectre described.

It stood and beckoned with its hand, as if calling him. He made a sign with his finger for it to wait a little, and again settled down to his tablets and style. It rattled its chains at his head as he wrote.

He looked up again, making the same sign as before, and without further delay took the candle and followed.

It walked with slow step, as if weighted with the chains. After turning into the courtyard of the house, it suddenly slipped into the earth and disappeared. He piled some weeds and leaves to mark the spot, and, the next day, going to the magistrates, advised them to order the place to be excavated.

A skeleton was found, the flesh all wasted away by putrefaction, and the bare bones bound in fetters and chains. It was taken up and publicly buried; and after that the house was no more troubled. [12]

It is possible to approach this legend from many folkloristic angles. Belief studies provide the folklorist with a toolkit for analysis of the tale in the context of Roman taboos and burial rituals. But even without this context, contemporary readers can readily detect elements of traditionality in the narrative itself. Something has gone wrong, and the spectre needs assistance from the living to make it right before he can move on. The narrative studies toolkit helps the folklorist identify and contextualize these traditional elements of the tale so that we can better understand legend motifs that appear across cultures and time periods. It also helps the folklorist analyze unique elements of the tale so that we can better understand nuances of Pliny the Younger’s culture and time. Finally, the performance studies toolkit enables the folklorist to understand Athenodorus’s presentation of self, [13] first as a skeptical philosopher legend-tripping in a haunted house [14] and then as a Roman citizen observing local burial customs. There is a great deal to unpack in this legend, especially as it regards traditionality in the narrative, which brings us to part of the toolkit folklorists use to study folk narratives and a deeper dive into Pliny the Younger’s ghost story itself.

4. Motifs & Tale Types

Folklorists analyze traditional narratives with a variety of tools, among them the Motif-Index of Folk-Literature and The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography (ATU index). [15] Both are helpful to understanding the individual units of meaning in a folktale and their arrangement, but both have limitations as well. Stith Thompson’s work in the Motif-Index is incomplete because Thompson was uncomfortable categorizing motifs he found obscene, [16] while the ATU index is somewhat Eurocentric even though Uther made an effort to correct this issue in the latest edition of the reference guide. [17][18] Still, as we will see, they are both powerful aids to analysis of traditional narratives.

For an example of this, let us return to Pliny the Younger’s legend. In it, the ghost is a unit of meaning, as are the philosopher, the chains, the haunted house, and many other aspects of the narrative. These small units of meaning are called motifs, and they are recorded among many thousands of others in Thompson’s Motif-Index. Using this index, we may observe that Pliny’s legend focuses on a ghost and that Ghost falls under E. The Dead and then E200-E599 Ghosts and Other Revenants. From there, we can zoom in further to find E280. Ghosts haunt buildings and finally to E281. Ghosts haunt house. This is our first motif. A second motif can be found nearby under E300-E399. Friendly return from the dead at E334.2.1. Ghost of murdered person haunts burial spot. Consider also E338.1. Non-malevolent ghost haunts house or castle, and under E400-E599 Ghosts and revenants - miscellaneous consider E410 The unquiet grave. [19]

Each of these entries in the Motif-Index provides a discussion of comparative material. This enables folklorists to extract information about the folktales containing the motif, including the various tales and versions of tales in which it appears. Finally, the Motif-Index also helps us understand how dissimilar narratives can be from one another. Imagine how emotionally and culturally different Pliny's story would be if it contained E.281.0.1. Ghost kills man who stays in haunted house, E384.2. Ghost raised inadvertently by whistling, or E321.3 Dead husband returns, asks wife to make him coffee. [20]

The ATU index categorizes larger units of meaning called tale types, which are the scaffolding or structure of traditional tales. Consider the following entry, which closely aligns with Pliny the Younger’s legend:

326A Soul Released from Torment. A poor soldier spends a night in a haunted house to earn a reward. He is not afraid of dragging chains, cries, falling limbs, etc. The soldier releases a restless spirit from punishment by his fearless behavior (by giving its ill-gotten gains to charity). He discovers a treasure (and may keep part of it for himself). [21]

Sound familiar? Yet there are also notable differences: in Pliny's telling, we do not meet a virtuous soldier. In ancient Rome, we follow the actions of a Classical philosopher, who watches carefully and acts both reasonably and stoically. Punishment of any kind does not appear to be a component of Pliny's tale, and we do not read of the philosopher receiving a treasure. We may wonder if the newly un-haunted house is to be considered a treasure or reward (from the gods?), whether Pliny left a treasure out, or if this variation in ATU 326A simply did not feature any kind of treasure at all.

Whatever the case, this makes for a helpful example of variation in time, place, and culture between folktales in a tale type. As Hans-Jörg Uther notes:

Each “tale type” presented [in the ATU tale type index] consists of a number, title, and a description of its contents, and must be understood to be flexible. It is not a constant unit of measure or a way to refer to lifeless material from the past. Instead, as part of a greater dynamic, it is adaptable, and can be integrated into new thematic compositions and media. [22]

This is exactly what we see with Pliny's ancient legend from pagan Rome. No one knows when or where this folktale first appeared. Chances are that it is older than Rome itself. But it survived longer than the Roman Empire did, circulating in the minds and mouths of humankind for thousands of years, as indicated by the examples outlined in ATU 326A.

We encourage readers to spend some time with both the Motif-Index of Folk-Literature and The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography. Until recently, the ATU index was exceptionally difficult to access, but that changed with the Kalevala Society's decision to release the latest edition (2011) to the public without charge, a move we strongly applaud. You can read the ATU index for free here. Unfortunately, the Motif-Index remains difficult to access, despite its importance and utility for both folklorists and non-folklorists. We hope that one day the copies on our shelves will become secondary to digital versions available to everyone.

5. Emic & Etic Approaches,

& Suggested Research Projects

Folklorists understand the value of emic and etic approaches to ethnographic research. An emic approach is an insider’s approach. You belong to the community, and you understand its nuances, so you come to the project with a greater awareness of interpersonal relationships, variations in expressive culture among members, and so on. Folklorists who conduct this sort of research understand that familiarity with a community can create biases and blind spots, so they are careful to interrogate these throughout the research and writing process. An etic approach is an outsider’s approach. You do not belong to the community, so you do not understand its nuances and need to discover them in the field. However, you may also bring fresh perspectives to the project because of this. You still have biases and blind spots, and they still need to be interrogated, but they arise from your unfamiliarity with the community. In both cases, folklorists are careful to declare their positionality in the field and in their scholarship, so people know what their relationship is to their community of interest.

With these approaches in mind, you might undertake a research project of your own. Here are a few suggestions:

Folklore Journaling: Keep a journal during the day. Every time you encounter folklore, make a note of it. The next day, compare your entries with the types of folklore outlined in any of the resources recommended below.

Interview a Family Member: Here is a chance to find family treasures! Spend time with elderly family members and ask them about traditional recipes, legends, or tales they remember. A good way to get the discussion flowing is to ask them about jokes, riddles, or games they knew from childhood. Record these conversations and transcribe them afterwards.

Archive Journeys: Archives are an important folklore resource because they document the everyday lives of people. Some archives are brick-and-mortar places you can visit to undertake folkloristic research, and others are on the Internet. Check your local area for physical archives, and check online for archives that might be digitized and available to the public. You might research supernatural beliefs in ghosts or hauntings, weather lore, historical recipes, or any other type of folklore that interests you.

Finally, keep the following research tips in mind:

Always Compare: When working with folklore materials in languages you do not speak, particularly ancient languages, consult at least a few different translations, and look for editions with as many supplementary notes as possible.

Who wrote this, and when?: Folklore scholarship is written by academic folklorists and anthropologists, and it tends to have a longer shelf-life than scientific scholarship. Still, knowledge-making is an ongoing process, and scholarship changes over time. So investigate the authors of the pieces you read to find out if they are qualified folklore researchers. In addition, if a particular piece you’re reading is more than thirty years old, look for newer scholarship on the topic and see if it complements or counters the older work.

Read and Review: Folklorists do not always agree with one another, and it is useful to consider the contrasting opinions of experts. With this in mind, read and review as much related scholarship as possible before coming to any conclusions about a topic.

6. A Few Misconceptions

Newcomers to folkloristics sometimes have misconceptions about folklore, and our goal here is to help clear up a few we encounter from time to time. The first of these is the mistaken belief that folkloristics is the study of traditional narratives and little else. As we have already noted, folklore is a big tent, and there are many kinds of historical and contemporary expressive culture in it. Myths are folklore, but so are insider jokes between transport truck drivers, personal experience narratives about adopted children, and the widespread belief that Dungeons & Dragons players should never roll with the dungeon master’s dice. Folklore is a renewable resource, continually recreated whenever and wherever humans communicate. So not only do we encounter folklore in everyday life, we make it as well.

Another misconception is that ghost-hunters and cryptozoologists are folklorists because they utilize specialist terminology, work with customized equipment, and present themselves as authorities on their topics of interest. It might be more helpful to think of ghost-hunters as legend-trippers: people who visit sites where supernatural sightings have been reported in the hope a ghost will appear while they are present. Cryptozoologists are similar in this way, seeking proof of folkloric creatures like Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster by investigating places they are purported to live. Academic folklorists are interested in the activities of these groups because they are compelling examples of expressive culture. After all, ghost-hunters and cryptozoologists are making folklore when they legend-trip and conduct investigations. However, these groups are not folklorists themselves.

A third misconception is tied to the relationship between regional folklore and political movements. In the early days of folkloristics, romantic nationalism motivated the collection of local folklore in an effort to propagate a sense of national history and unity. Contemporary academic folklorists study this history of the discipline and know how to avoid the pitfalls of romantic nationalism in their work. However, the importance of emic scholarship to the discipline means that academic folklorists often study political and social issues they care about and take positions on these issues in their writing. However, and as we have previously mentioned, they are also trained to declare these emic positions at the outset so the reader is aware of them. This is important to know because there are many political and social organizations that utilize folklore in the service of their agendas. Flags (material culture), anthems (folk song), heroic and patriotic stories (folk narrative), and other folkloric elements of political and social culture are often used to influence the public in subtle ways, without the straightforward declaration of position the academic folklorist provides.

A final misconception is that US writer Joseph Campbell (d. 1987) was a folklorist because he wrote about myth. His “Hero’s Journey” was and remains the backbone of many movie scripts and novels, and he was the topic of various documentaries. However, Joseph Campbell was not a folklorist. Indeed, Campbell’s construction of the "monomyth" and "Hero's Journey" were met with rejection from folklorists, including Alan Dundes, who writes:

It has long been a popular fantasy among amateur students of myth that all peoples share the same stories. This is clearly an example of wishful thinking. Campbell referred to the hero pattern as a universal monomyth, borrowing this vacuous portmanteau neologism from Joyce's Finnegan's Wake ... On the universality issue, the empirical facts suggest otherwise. There is not one single myth that is universal, a statement that runs counter to Campbell's view. … Even a beginning student of folklore could dispute this kind of argument by assertion. It is easy to make ex cathedra pronouncements about universals, but it is quite difficult to document them. Take the virgin birth, for example. If we look in the Motif-Index, we find Motif T547, Birth from Virgin, with just three citations listed for the motif. One refers to European saints, another to a classical Greek myth, and one to a South American source. Period. (23)

Dundes goes on to provide a variety of examples demonstrating the complications that arise from theorizing about 'universal' motifs, drawing examples from Campbell's claims. So while Joseph Campbell’s ideas are attractive and popular with script writers and novelists, they are not rooted in folkloristics.

7. Reading and Resources

Academic folklorists are a diverse group of people who engage with folkloristics for many different reasons. To learn more about them, we recommend this excellent series of videos by the American Folklore Society titled “Why I’m a Folklorist." In it, American folklorists introduce themselves and discuss why they decided to pursue education and employment in the field. There are folklorists active all over the world as well, pursuing folkloristic and ethnographic inquiries that both resemble and depart from those of their American colleagues. Folkloristics is a big tent, indeed. Below we provide a variety of resources for pursuing folklore in any number of directions. Please note that this list is non-comprehensive and is aimed primarily at English language resources.

A. Educational institutions

Canada

Memorial University of Newfoundland Folklore Department: Offers PhDs in Folklore and Ethnomusicology

Université Laval Department of Historical Sciences: Offers a PhD in Ethnology and Heritage (Taught in French)

United States

George Mason University: Offers a Master’s Degree in Folklore

Indiana University Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology: Offers PhDs in Folklore and Ethnomusicology

Ohio State University's Center for Folklore Studies: Offers Students in the English and Comparative Studies Departments a Range of Courses in Folklore

University of Oregon Folklore and Public Culture Program: Offers a Master’s Degree in Folklore and Public Culture

Utah State University: Offers an MA and MS in Folklore Studies

Europe

The Rijksuniversiteit in Groningen, the Netherlands, provides a basic Dutch Folklore class in their Dutch Studies Programme.

The University of Hertfordshire, England: Offers a Master’s Degree in Folklore Studies

University of Helsinki, Finland, Folklore Studies: Offers a Master’s Program in Cultural Heritage (Taught in Finnish)

B. Folklore Studies Organizations and Journals

There are many folklore studies organizations and journals. Here are just a few:

C. Research Databases

D. Podcasts

There are a lot of great folklore podcasts out there! Check out Hyldyr’s list of some of them here.

E. Other Online Resources

Academia.edu: Many scholars upload papers to Academia.edu, which makes it an important stop for any research project, even though many facets of this website, it must be said, need major improvement and are obnoxiously monetized.

Archive.org: An excellent resource for out-of-print folklore texts, especially folk narrative collections.

Fife Folklore Archives at Utah State University: “The Fife Folklore Archives (FFA) is one of the largest repositories of American folklore in the United States.”

Google Books: A database containing scans of many thousands of books from a plethora of libraries, including otherwise difficult-to-access items like this 17th century source.

Google Scholar: A source for finding papers written by specific scholars. Worth using in any deep dive for material.

JSTOR: A database of papers from scholars. This resource is the least open-access of all those we have provided, but it does allow for limited viewing of papers. If you’re looking for access to a peer-reviewed paper in the field, there’s a good chance that it is here.

National Folklore Collection (Ireland): A large archive of Irish folklore available to the public

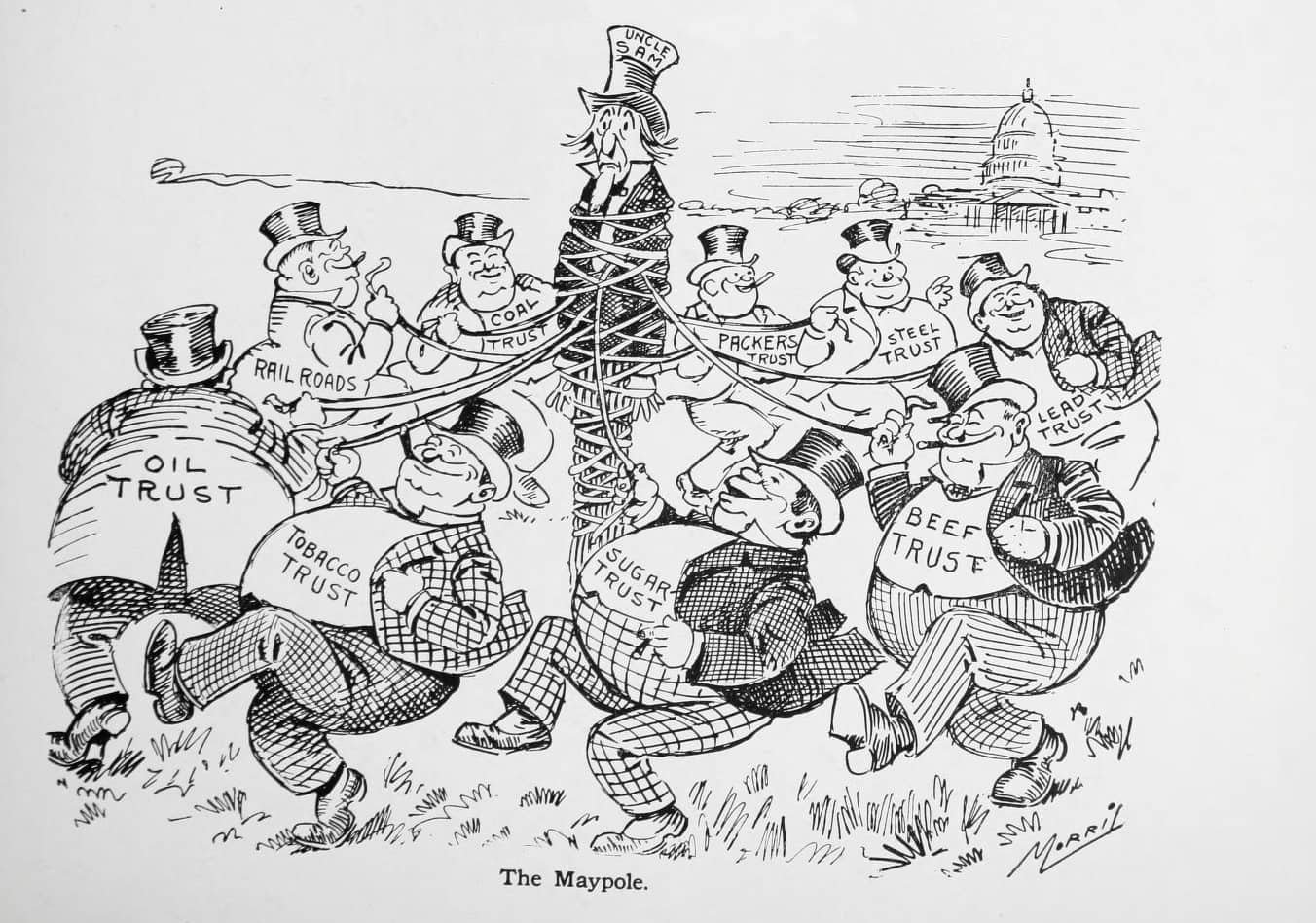

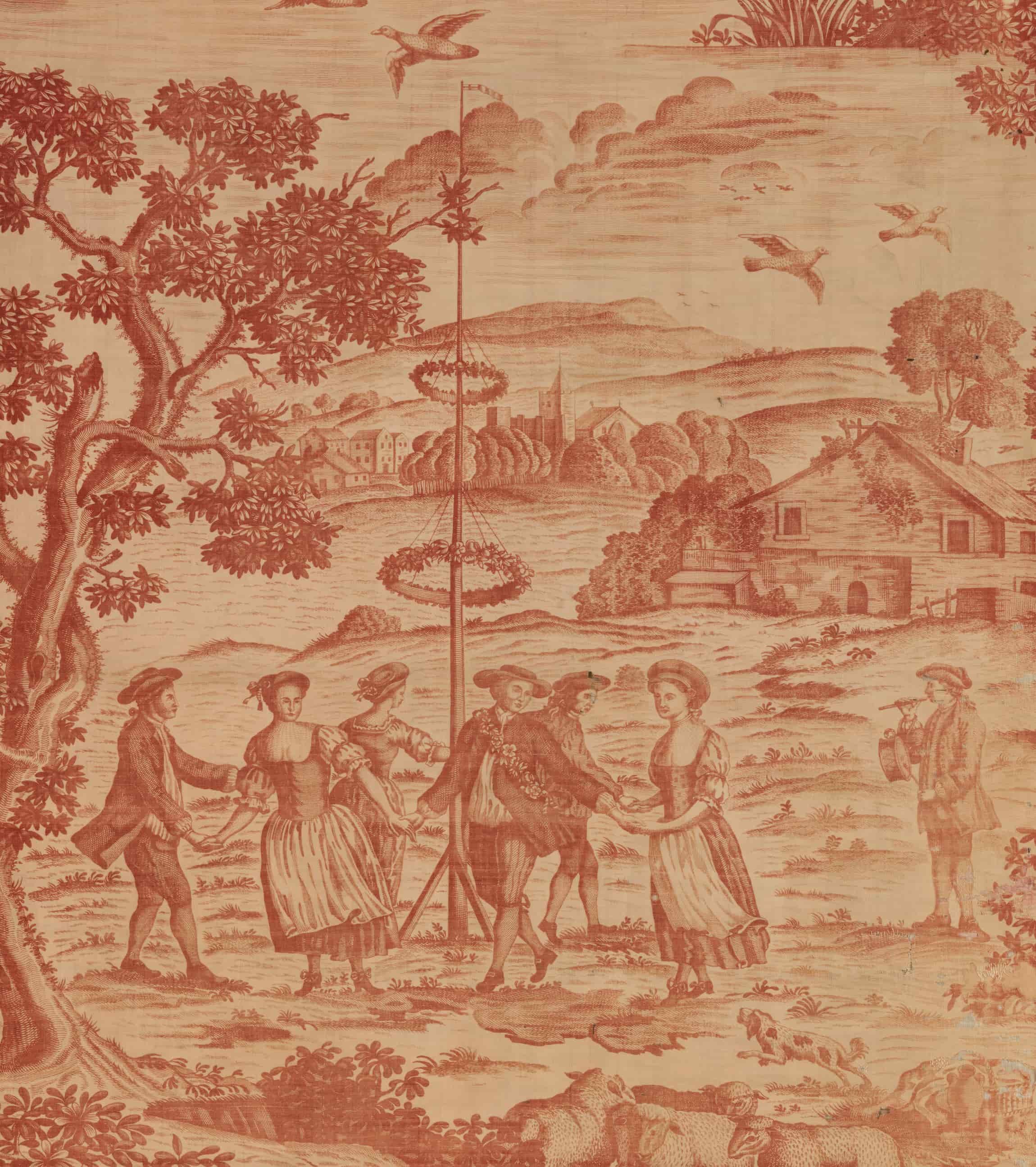

8. About the Art

To assist in navigating this page and to add visual distinction, we’ve added various depictions and photographs of the folk practice of erecting and dancing around maypoles through the years to some of the background sections between divisions.

The images are as follows:

Geoff Charles, 1941. "Teitl Cymraeg". The National Library of Wales via Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Llanfyllin_carnival_and_maypole_(7131389767).jpg

Pieter Brueghel the Younger. Date unclear: 1500s. "St. George's Kermis with the Dance around the Maypole". Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St._George's_Kermis_with_the_Dance_around_the_Maypole_by_Pieter_Brueghel_the_Younger.jpg

Carl Millner. 1848. "Maibaumfest" (?). Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Carl_Millner_Maibaumfest_1848.jpg

Gaspar de Witte. Date unclear: 1654-1681. "Elegant figures on a boating lake, allegory of spring". Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gaspar_de_Witte_-_Elegant_figures_on_a_boating_lake,_an_allegory_of_spring.jpg

"The Worker's Maypole" by Walter Crane, 1894. Derived from the following URL: https://www.betweenthecovers.com/pages/books/562379/walter-crane/broadside-the-workers-maypole

"Dancers around the May pole at Western College on Tree Day", 1916. Miami University Libraries - Digital Collections via Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dancers_around_the_May_pole_at_Western_College_on_Tree_Day_1916_(3190849017).jpg

Editorial cartoon by William C. Morris as published in The Spokesman-Review, 1908. Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WCMorris_Spokesman-Review_cartoons_123.jpg

Marion Post Walcott, 1939. "School children rehearsing Maypole festivity, in Gee's Bend, Alabama, 1939". United States Farm Security Administration. Wikimedia Commons:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Maypole_festivity,_Alabama_(1939).jpg

"The Maypole", artist unknown, 1770. The Met: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/221990

Paulus van Liender, 1761. "Het Dorp Wenekendonk 1739". Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Het_Dorp_Wenekendonk_1739.jpg

9. Notes & Works Cited

Ben-Amos, Dan. “Toward a Definition of Folklore in Context.” In Towards New Perspectives in Folklore. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1972: 9.

Dundes, Alan. 2005. “Folkloristics in the Twenty-First Century (AFS Invited Presidential Plenary Address, 2004).” The Journal of American Folklore 118, no. 470: 385–408: 3.

Ben-Amos, Dan. “Toward a Definition of Folklore in Context.” In Towards New Perspectives in Folklore. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1972: 9.

“Folkloristics” refers to the academic study of folklore.

For discussion of many more definitions offered for the field, see: Dundes, Alan. 1965. The Study of Folklore. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall: 1-52.

For an excellent discussion of ghosts in the context of narratives provided by widows about their deceased husbands, see: Bennett, Gillian. 1999. Alas, Poor Ghost! Traditions of Belief in Story and Discourse. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Hufford, David. 1982. “Traditions of Disbelief.” New York Folklore Quarterly 8: 47–55.

A memorate is a personal experience narrative with a supernatural component.

Early speakers of the Germanic languages lived in the several centuries before and after the first century.

As reconstructed by Kroonen, we expect the unattested noun form Proto-Germanic *gaista-, see: Kroonen, Guus (2013). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Germanic. Brill: 163

Sadly, no narratives from early Germanic languages narratives make their way to us—directly, at least.

Dallas, Eneas Sweetland. 1869. Once a Week. London: Thomas Cooper and Co: 143-144.

Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Garden City: Doubleday.

Readers may detect a distant precursor in the tale to contemporary housing prices for homes purported to be haunted and the ways they are stigmatized.

So called because it is the culmination of Antti Aarne’s, Stith Thompson’s, and Hans-Jörg Uther’s work.

Dundes, Alan. 1997. “The Motif-Index and the Tale Type Index: A Critique.” Journal of Folklore Research 34, no. 3 (September): 195–202: 198.

Hans Jörg Uther, The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography. Part 1: Animal Tales, Tales of Magic, Religious Tales, and Realistic Tales, with an Introduction (Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, 2011): 11.

Folklorists have produced many new motif and tale type entries in secondary literature over the years, which has also helped to address this concern.

Thompson, Stith. 1957. Motif-Index of Folk-Literature Volume Two D-E. Bloomington: Indiana University Press: 419-440.

Ibid.

Uther, Hans Jörg. 2011. The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography. Part 1: Animal Tales, Tales of Magic, Religious Tales, and Realistic Tales, with an Introduction. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia: 210.

Uther, Hans Jörg. 2011. The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography. Part 1: Animal Tales, Tales of Magic, Religious Tales, and Realistic Tales, with an Introduction. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia: 8.

Dundes, Alan. 2005. “Folkloristics in the Twenty-First Century (AFS Invited Presidential Plenary Address, 2004).” The Journal of American Folklore 118, no. 470: 395-396.

It may also be possible for exchange students to follow only that course.